When Kay and David Root purchased waterfront acreage to build a vacation home in 1988, their original plan didn’t include living year-round in the century-old summer resort town of Harbor Springs. Yet nearly 20 years later, they are hard-pressed to leave the magical spot they have developed into a comfortable residence, guesthouse and artist’s studio, all of which provide magnificent views of Little Traverse Bay on northern Lake Michigan.

But this is the story of their “entertainment pavilion,” an Adirondack-style open-air log structure tucked far into the woods. When the Roots lead unknowing guests there via a wooden boardwalk across a swamp, the secret destination takes their breath away.

Using the swampland

The swamp is wetland property the Roots owned for nearly a decade before convincing Michigan’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) that their plan for building wouldn’t impact sensitive wetlands.

“When we purchased our waterfront,” says Kay, “it came with the adjacent swamp acreage behind the house and across the road.”

David got permission to build a footpath across the wetland that ended at a platform where the Roots placed some outdoor furniture. But soon that wasn’t enough of a destination for him, and he went back to the DEQ with his idea for the pavilion.

David Root is an avid historian, and his vision for the Adirondack style structure was based on extensive research of rustic summer lake camps and seasonal resorts built for wealthy New Yorkers deep in the North Woods in the late 1800s. He sketched his ideas and then handed the project to his next-door neighbor, residential architect Fred Ball, to refine the details.

Creating something special

Fortunately, Ball shared Root’s enthusiasm for early cottage architecture, so the two were perfectly in tune. And Ball had just returned from Cashiers, N.C., where the Chatooga Croquet Club has an immense outdoor pavilion that provided further inspiration for the Roots’ project.

“I love the pavilion,” says Ball. “It’s really quite a shock when you see it. You’re walking along this wetland path, then entering the woods, which open up to a clearing, and bam – there it is!”

The structure looks like it’s been there forever, says Ball, and it’s not so different from the summer places that have been built in northern Michigan for at least a hundred years. The pavilion is wide open to the elements on three sides and all the materials are indigenous to the area.

“But the real beauty of it,” says Ball, “is that it’s so ... whimsical. I’m always designing buildings that are necessary – never just for fun.”

But this is the story of their “entertainment pavilion,” an Adirondack-style open-air log structure tucked far into the woods. When the Roots lead unknowing guests there via a wooden boardwalk across a swamp, the secret destination takes their breath away.

Using the swampland

The swamp is wetland property the Roots owned for nearly a decade before convincing Michigan’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) that their plan for building wouldn’t impact sensitive wetlands.

“When we purchased our waterfront,” says Kay, “it came with the adjacent swamp acreage behind the house and across the road.”

David got permission to build a footpath across the wetland that ended at a platform where the Roots placed some outdoor furniture. But soon that wasn’t enough of a destination for him, and he went back to the DEQ with his idea for the pavilion.

David Root is an avid historian, and his vision for the Adirondack style structure was based on extensive research of rustic summer lake camps and seasonal resorts built for wealthy New Yorkers deep in the North Woods in the late 1800s. He sketched his ideas and then handed the project to his next-door neighbor, residential architect Fred Ball, to refine the details.

Creating something special

Fortunately, Ball shared Root’s enthusiasm for early cottage architecture, so the two were perfectly in tune. And Ball had just returned from Cashiers, N.C., where the Chatooga Croquet Club has an immense outdoor pavilion that provided further inspiration for the Roots’ project.

“I love the pavilion,” says Ball. “It’s really quite a shock when you see it. You’re walking along this wetland path, then entering the woods, which open up to a clearing, and bam – there it is!”

The structure looks like it’s been there forever, says Ball, and it’s not so different from the summer places that have been built in northern Michigan for at least a hundred years. The pavilion is wide open to the elements on three sides and all the materials are indigenous to the area.

“But the real beauty of it,” says Ball, “is that it’s so ... whimsical. I’m always designing buildings that are necessary – never just for fun.”

A craftsman's touch

After Root and Ball agreed on the design criterion, the entire project was handed off to local artisan and builder Andre Poineau, who is well known in the Great Lakes region for his custom residences that are rich in hand craftsmanship.

One of the defining details of the pavilion is a handmade sumac twig railing that leads up a multi-level stairway to the main floor and surrounds the perimeter of the 16-foot by 24-foot space. Each section of delicate sumac twig was hand-carved, carefully scribed and wrapped around the white cedar uprights, with no visible joinery. “Every piece was meticulously pegged and screwed with hidden fasteners. We even kept a mallet that they made especially for this project,” says Kay Root.

Because the structure is near a wetland, the Roots took care to site it carefully.

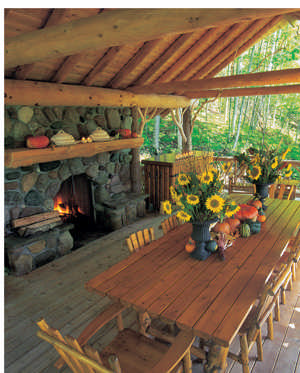

Although concrete pads were poured underground to support 10 hefty 14-inch support beams of natural Michigan white fir, no concrete shows since everything is faced in Michigan fieldstone. An enormous open fireplace of the same fieldstone, full of moss and lichens, centers the room and is topped by a massive timber mantel.

“If you look carefully, you can see that the four guys who built the pavilion carved their names in one end of the mantel,” says Kay. “You know, this was really an art project more than a construction project, so we love that. When you’re building art, you should sign your work.” The stone hearth provides the only source of heat and light, except for lots of candles when the Roots entertain.

After Root and Ball agreed on the design criterion, the entire project was handed off to local artisan and builder Andre Poineau, who is well known in the Great Lakes region for his custom residences that are rich in hand craftsmanship.

One of the defining details of the pavilion is a handmade sumac twig railing that leads up a multi-level stairway to the main floor and surrounds the perimeter of the 16-foot by 24-foot space. Each section of delicate sumac twig was hand-carved, carefully scribed and wrapped around the white cedar uprights, with no visible joinery. “Every piece was meticulously pegged and screwed with hidden fasteners. We even kept a mallet that they made especially for this project,” says Kay Root.

Because the structure is near a wetland, the Roots took care to site it carefully.

Although concrete pads were poured underground to support 10 hefty 14-inch support beams of natural Michigan white fir, no concrete shows since everything is faced in Michigan fieldstone. An enormous open fireplace of the same fieldstone, full of moss and lichens, centers the room and is topped by a massive timber mantel.

“If you look carefully, you can see that the four guys who built the pavilion carved their names in one end of the mantel,” says Kay. “You know, this was really an art project more than a construction project, so we love that. When you’re building art, you should sign your work.” The stone hearth provides the only source of heat and light, except for lots of candles when the Roots entertain.

A place for entertaining

The long, handmade trestle table situated in front of the fireplace in the pavilion has seen many parties and celebrations: festive catered breakfasts prior to pheasant hunting outings, cocktail parties and old-fashioned picnics in baskets.

Silverware and dishes are stored in “bear safes” – two large padlocked trunks made of unpeeled logs that keep out wildlife and also double as buffet space.

Root even designed a little red wagon with a striped surrey that hitches to a cooler on wheels to cart food and beverages from their house down the quarter-mile boardwalk to the pavilion.

“It does take some doing,” admits Kay with a laugh, “so we try to keep everything as easy as possible. On occasion, we may use a charcoal grill that is stored up there, but because we haven’t any utilities or kitchen, nearly everything else must be prepared in advance.” She favors large platters of simply grilled meats and vegetables served at room temperature.

A place for getting away

But the thing she loves best about the pavilion may not be the parties.

“It makes for a good walk, so I go up there nearly every day,” Kay says. “It’s a refuge, a resting place; it’s very therapeutic.

“In northern Michigan, everyone is always focused on the lake. Then you go back there, and it’s a whole different world, but every bit as wonderful. It’s almost spiritual.

“I see it happen with other people I bring there, too. Everyone gets very quiet. I’ve had deer come right up to me, which is the most awesome experience, to have an animal totally trust you. But it could only happen in a place like that.”

Every season of the year in northern Michigan provides interactions with new wildlife, and what began as a summer house is now the center of the Roots’ lives. “We love our year-round life here,” says Kay, adding, “We just feel so grateful to have this chance … to have a spot that takes us back to a simpler time and gives us some moments of peace.”

Robyn Cannon is a Seattle-based writer. She often works from an Adirondack chair in her garden overlooking Puget Sound, while her Tibetan Terrier, Scarlett, edits copy for cookies.

The long, handmade trestle table situated in front of the fireplace in the pavilion has seen many parties and celebrations: festive catered breakfasts prior to pheasant hunting outings, cocktail parties and old-fashioned picnics in baskets.

Silverware and dishes are stored in “bear safes” – two large padlocked trunks made of unpeeled logs that keep out wildlife and also double as buffet space.

Root even designed a little red wagon with a striped surrey that hitches to a cooler on wheels to cart food and beverages from their house down the quarter-mile boardwalk to the pavilion.

“It does take some doing,” admits Kay with a laugh, “so we try to keep everything as easy as possible. On occasion, we may use a charcoal grill that is stored up there, but because we haven’t any utilities or kitchen, nearly everything else must be prepared in advance.” She favors large platters of simply grilled meats and vegetables served at room temperature.

A place for getting away

But the thing she loves best about the pavilion may not be the parties.

“It makes for a good walk, so I go up there nearly every day,” Kay says. “It’s a refuge, a resting place; it’s very therapeutic.

“In northern Michigan, everyone is always focused on the lake. Then you go back there, and it’s a whole different world, but every bit as wonderful. It’s almost spiritual.

“I see it happen with other people I bring there, too. Everyone gets very quiet. I’ve had deer come right up to me, which is the most awesome experience, to have an animal totally trust you. But it could only happen in a place like that.”

Every season of the year in northern Michigan provides interactions with new wildlife, and what began as a summer house is now the center of the Roots’ lives. “We love our year-round life here,” says Kay, adding, “We just feel so grateful to have this chance … to have a spot that takes us back to a simpler time and gives us some moments of peace.”

Robyn Cannon is a Seattle-based writer. She often works from an Adirondack chair in her garden overlooking Puget Sound, while her Tibetan Terrier, Scarlett, edits copy for cookies.

Creating Adirondack Architecture

Adirondack style began more than a century ago when architect William West Durant created rustic estates in the North Woods for his wealthy New York clients. In many ways, it is an organic art form and each project is unique unto itself because it relies solely on natural materials.

But historically, there are certain design principles that should be observed in order for it to be considered true to form. Here are some considerations for incorporating authentic Adirondack design into your own retreat:

The Adirondack style represents a harmony between the woods and man-made structures. Keep it simple and rustic, and when you site your structure, try to disturb its surroundings as little as possible.

Use natural stone and logs that are indigenous to your region. You can adapt this historic style, but be careful not to import materials that are not found locally.

You’ll want your building to gradually age to “fit,” acquiring a soft patina that matches the surrounding landscape. If the wood is treated for weatherproofing reasons, it should be undetectable to the eye.

Traditionally, roofs are shingled or prairie board and batten, and are painted or stained a dark green. A dash of color – usually red – might only be seen on window frames, to provide an occasional contrast to an otherwise neutral palette.

Find an architect and local craftsman who love and understand the art of Adirondack design. Your architect will know ways of incorporating modern technology (for example, rubber ice shield on the roof or dimensional lumber that looks natural) without destroying the authenticity of the style. Use your imagination to incorporate rustic features like peeled bark sheathing, elaborate branch-work patterns on porch railings, shingled roofs with broad overhangs.

Choose local fieldstone for foundation work, walls and chimneys. Look for stone boulders that have been aging in a farmer’s field and have gathered years of lichens and moss, instead of “pit run” fieldstone that is dug and smooth.

You can see some of the finest examples of Adirondack architecture in our National Parks lodges. President Theodore Roosevelt created the National Parks system and believed that the structures within the parks would be most appropriate if they emulated this style. Today, we are lucky to still have magnificent lodges in the Adirondack tradition. One of the best is The Inn at Old Faithful in Yellowstone National Park. It remains the largest frame structure in the world, and the massive timbers were all gathered from within the park!

Adirondack style began more than a century ago when architect William West Durant created rustic estates in the North Woods for his wealthy New York clients. In many ways, it is an organic art form and each project is unique unto itself because it relies solely on natural materials.

But historically, there are certain design principles that should be observed in order for it to be considered true to form. Here are some considerations for incorporating authentic Adirondack design into your own retreat:

The Adirondack style represents a harmony between the woods and man-made structures. Keep it simple and rustic, and when you site your structure, try to disturb its surroundings as little as possible.

Use natural stone and logs that are indigenous to your region. You can adapt this historic style, but be careful not to import materials that are not found locally.

You’ll want your building to gradually age to “fit,” acquiring a soft patina that matches the surrounding landscape. If the wood is treated for weatherproofing reasons, it should be undetectable to the eye.

Traditionally, roofs are shingled or prairie board and batten, and are painted or stained a dark green. A dash of color – usually red – might only be seen on window frames, to provide an occasional contrast to an otherwise neutral palette.

Find an architect and local craftsman who love and understand the art of Adirondack design. Your architect will know ways of incorporating modern technology (for example, rubber ice shield on the roof or dimensional lumber that looks natural) without destroying the authenticity of the style. Use your imagination to incorporate rustic features like peeled bark sheathing, elaborate branch-work patterns on porch railings, shingled roofs with broad overhangs.

Choose local fieldstone for foundation work, walls and chimneys. Look for stone boulders that have been aging in a farmer’s field and have gathered years of lichens and moss, instead of “pit run” fieldstone that is dug and smooth.

You can see some of the finest examples of Adirondack architecture in our National Parks lodges. President Theodore Roosevelt created the National Parks system and believed that the structures within the parks would be most appropriate if they emulated this style. Today, we are lucky to still have magnificent lodges in the Adirondack tradition. One of the best is The Inn at Old Faithful in Yellowstone National Park. It remains the largest frame structure in the world, and the massive timbers were all gathered from within the park!

Andrew Buchanan/SLP

Andrew Buchanan/SLP

Andrew Buchanan/SLP

Andrew Buchanan/SLP